The Twin Challenges for Maternal and Child Health in India: Iron & Proteins, and Technology driven Local Solutions

Author – Dr.Bhaskar Datta, Associate Professor, Chemistry and Biological Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, India.

India accounts for the highest number of undernourished people in the world totalling close to 200 million. Steady improvements have been made between 2004-06 and 2018-20 with India recording one of the highest reductions in total number of undernourished in Southern Asia. Malnourishment is a multi-factorial challenge and the steady reduction in total number of malnourished individuals points to overall improvements in health practices and access to clean water and nutritious food. Nevertheless, the most profound effects of malnourishment are observed in children below 5 years and women of reproductive age. Nearly 30% children in the 0-5 year age-group are stunted while 53% women are affected by varying degree of anaemia.

India accounts for the highest number of undernourished people in the world totalling close to 200 million. Steady improvements have been made between 2004-06 and 2018-20 with India recording one of the highest reductions in total number of undernourished in Southern Asia. Malnourishment is a multi-factorial challenge and the steady reduction in total number of malnourished individuals points to overall improvements in health practices and access to clean water and nutritious food. Nevertheless, the most profound effects of malnourishment are observed in children below 5 years and women of reproductive age. Nearly 30% children in the 0-5 year age-group are stunted while 53% women are affected by varying degree of anaemia.

The distribution of undernourishment is heterogeneous across the country. Interestingly, while the prevalence of stunting and underweight in children has decreased over the past 5 years, the total number of anaemic individuals has increased. These trends could be attributed to macro- and micronutrient intake with fewer than 1/3rd of all women consuming adequate amounts of both. Consumption of macronutrients in the form of carbohydrates and proteins is consistently below the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) levels prescribed by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR). The household consumption of micronutrients in the form of vitamins and minerals such as iron ranges from inadequate to severely deficient. Iron deficiency is associated with the majority of anaemia prevalent in India. A mind-boggling 67% of children in 2019-21 had varying degrees of anaemia, an increase of 8% from 2015-16.

The distribution of undernourishment is heterogeneous across the country. Interestingly, while the prevalence of stunting and underweight in children has decreased over the past 5 years, the total number of anaemic individuals has increased. These trends could be attributed to macro- and micronutrient intake with fewer than 1/3rd of all women consuming adequate amounts of both. Consumption of macronutrients in the form of carbohydrates and proteins is consistently below the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) levels prescribed by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR). The household consumption of micronutrients in the form of vitamins and minerals such as iron ranges from inadequate to severely deficient. Iron deficiency is associated with the majority of anaemia prevalent in India. A mind-boggling 67% of children in 2019-21 had varying degrees of anaemia, an increase of 8% from 2015-16.

Advances in industrial food processing with an emphasis on “food safety”, but not nutrition, has produced an ecosystem of inexpensive processed foods. The World Health Organization (WHO) has qualified undernourishment as protein energy malnutrition, to better explain the imbalance in supply of protein and energy with the body’s demands. The consumption of disproportionately high levels of processed sugars and saturated fats has resulted in a sharp increase in obesity in children and young adults especially in urban centres. The sub-optimal levels of macro- and micronutrients in diet is ultimately associated with chronic non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes.

Notably, while the country has witnessed a systematic strengthening of policies governing food safety, nutritional security is yet to experience as much vibrancy. Considering the massive number of women and children in India who face severe macro- and micronutrient deficiencies, a case is to be made for looking beyond the simple prescription of healthy diet plans and eating habits. Innovations that allow “health foods” to be accessible for all economic segments of India are likely to address the challenges in nutrition while aligning with current global market forces. To begin with, protein and iron would be ideal core ingredients in such innovations.

It took a global pandemic to energize discussions surrounding nutritious food. People’s engagement in culinary activities and food entrepreneurship was visible throughout the pandemic-related disruptions. For some, this was a hobby that could be affordably pursued in one’s home. For many others, this emerged as a vital source of income and employment.

While food entrepreneurship during the pandemic relied heavily on innovations in logistics, an emphasis on healthy products was widely evident. The buzz around health foods during covid-19 was a reminder that ‘unhealthy foods’ are all around us, enjoying huge market share among consumers from across all geographic, demographic and economic classifications.

Over the past two decades, codification of food safety norms in the country and alignment with global standards such as in labelling of packaged foods have gradually improved consumer confidence. One example of enlightened food manufacturing is the fortification of packaged grains, cereals and oils with micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Further, the Indian government has announced that all rice distributed under public food security schemes will be fortified with iron and folic acid by 2024. In spite of these positive developments, two key aspects of food entrepreneurship and manufacturing need to be rejuvenated.

Over the past two decades, codification of food safety norms in the country and alignment with global standards such as in labelling of packaged foods have gradually improved consumer confidence. One example of enlightened food manufacturing is the fortification of packaged grains, cereals and oils with micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals. Further, the Indian government has announced that all rice distributed under public food security schemes will be fortified with iron and folic acid by 2024. In spite of these positive developments, two key aspects of food entrepreneurship and manufacturing need to be rejuvenated.

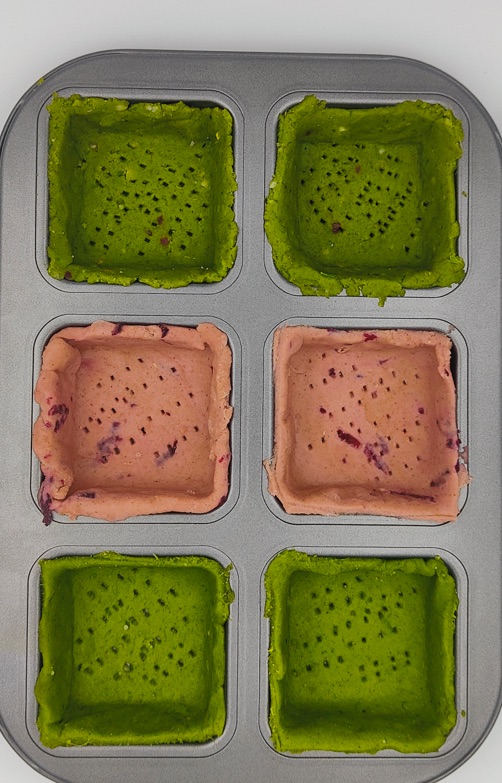

First, entrepreneurial efforts emerging from economically weaker sections need access to scientific and technological inputs to develop knowledge-driven products. Ventures that are commercializing cultural legacy food products may have a straightforward and assured revenue generation model but are unlikely to be competitive in nutritional value and market reach. For example, women microentrepreneurs in a low-income community preparing packaged farsan are unlikely to face challenges in product placement in their neighbourhoods. If the same group could develop a protein-rich and iron-containing farsan, they could also address the nutritional requirements of their primary consumers. In doing so, it is possible that their manufacturing and processing techniques need to be revised for enhanced nutritional value of ingredients and avoid unsafe handling practices in their complete supply chain.

Large numbers of women in such socio-cultural contexts manage the food habits of their entire family. Training women microentrepreneurs in the art of assimilating scientific inputs is likely to amplify good health practices in their immediate families. Second, entrepreneurial efforts emerging from economically affluent sections need to be inclusive of customers from across all economic backgrounds. It is not uncommon to see a child of migrant labourers living significantly below poverty line eating a bag of purchased branded potato chips. If this kid can be happier, eating a similarly purchased bag of ‘health food’ with suitable amounts of protein and iron, it would signal a successful convergence of food safety and nutrition. Both of the above aspects require deep and pro-active engagement of food scientists and professionals. These could be further facilitated by academic and research institutions that identify challenges faced by the entrepreneurs as possibilities for collaborative problem-solving.

Large numbers of women in such socio-cultural contexts manage the food habits of their entire family. Training women microentrepreneurs in the art of assimilating scientific inputs is likely to amplify good health practices in their immediate families. Second, entrepreneurial efforts emerging from economically affluent sections need to be inclusive of customers from across all economic backgrounds. It is not uncommon to see a child of migrant labourers living significantly below poverty line eating a bag of purchased branded potato chips. If this kid can be happier, eating a similarly purchased bag of ‘health food’ with suitable amounts of protein and iron, it would signal a successful convergence of food safety and nutrition. Both of the above aspects require deep and pro-active engagement of food scientists and professionals. These could be further facilitated by academic and research institutions that identify challenges faced by the entrepreneurs as possibilities for collaborative problem-solving.

Food products that combine cultural culinary practices with scientific and technological inputs are likely to fulfil grassroots efforts to address prominent health challenges in the country, including the deficiency of iron and proteins among women and children. This will also generate local enterprises and a local circular economy, ensuring longterm sustainability and replicability.

Dr. Bhaskar Datta is an Associate Professor, Chemistry (jointly with Biological Engineering) at the Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, India. His group is working on developing protein and micronutrient-rich foods, in addition to other research projects in food. He can be contacted by clicking here